The Black Mirror of History: What the Popular Series Name Meant 300 Years Ago

The mysterious metaphor in the title of the internationally popular TV series, Black Mirror has bugged its fans for a long time. Contrary to certain theories that the title refers to the ‘dark side’ of reality, ‘black mirror’ actually represents a turned off smartphone or computer screen in which users see their own reflection. However, what many people don’t know is that the concept of a black mirror existed long before modern technology, dating as far back as the middle of the 18th century.

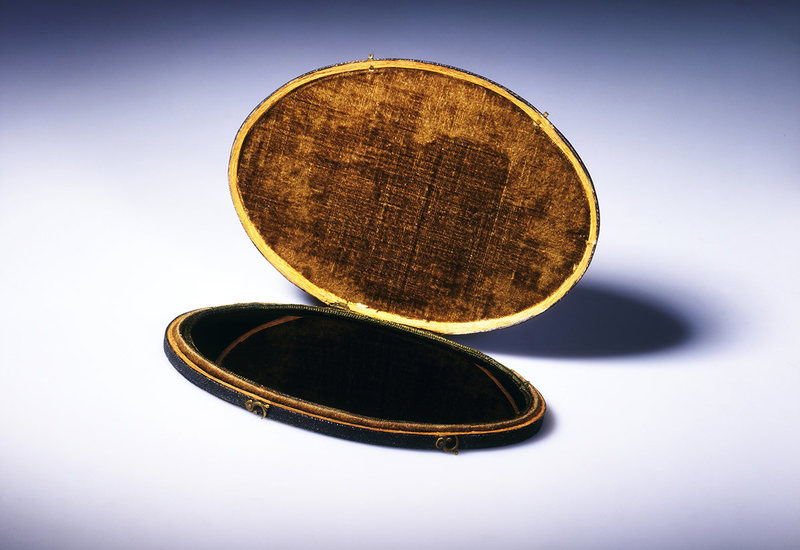

Black mirrors were popular with artists — particularly British artists during the 18th and 19th centuries — and art connoisseurs, who would take such accessories on walks and plein airs. They were small, dark and slightly curved, meaning that they could collect reflected objects into a single picture and simplify its tonal range. The image thus obtained was reminiscent of paintings by the famous French landscape painter, Claude Lorrain (1600–1682) so the mirrors became known as ‘Claude glass’.

William Gilpin (1724–1804), the originator of the picturesque style that became the cornerstone of 18th century English aesthetics, worked in a similar manner. Gilpin rejected the art world’s previously established ideas of symmetry and rationality, believing instead that the sight is attracted to natural light and shadow, curved lines, and a certain formlessness — such as that seen in the English landscape. It is possible that Gilpin himself used a black mirror for sketching from life. Made by Gilpin according to his own drawings, his oval shaped aquatines — known as picturesque tours — are remarkable. Gilpin was even known to use a coloured Claude glass, through which he looked at and captured the landscape.

Shaded mirrors and coloured glass were also popular amongst travellers who were interested in the idea of ‘scenic tourism’ (so-called ‘picturesque tourists’). The English poet, Thomas Gray (1716–1771) was fond of taking them on walks, as evidenced by his travel notes. One entry in Gray’s journal mentions grey-coloured glass that he used for watching the sunset. It was reported that the poet was once so taken with what he saw in the glass that he lost his footing, fell and broke his arm.

Some travel guides of the period recommended certain locations to see using a black mirror. Such publications included An Influential Guide to the Lakes by Thomas West (1720-1779), which was published in 1778. The guide recommends that travellers carry two mirrors when visiting the area: one for large and close objects and another with an increase, which could be used to view smaller or distant objects.

Despite their popularity with artistic minds of the day, not everyone was a fan of the black mirror and coloured glass. Notable artist and art theorist, John Ruskin (1819–1900) famously called Claude glass “one of the most pernicious tools of falsifying reality”. The mirror was often ridiculed, most notably in a parody poem by William Combe (1741–1823). Published in 1812, The Tour of Doctor Syntax: In Search of the Picturesque follows the adventures of a picturesque tourist who has ambitions — like Gray or West before him — to write about his travels and become famous. He searched for such inspirational landscapes and images in a darkened mirror, but due to being unable to take his eyes off what he saw he was constantly running into obstacles, falling from a horse on the move and even walking into a lake.

Combe’s character claimed to perceive the world, but instead of looking around he was instead fixated on what he saw in the mirror — a description that would fit today’s social media and Instagram users. The 20th century writer and book critic, Hugh Sykes Davies (1909–1984) once laughed at artists who, in order to depict an object, turned their backs on it, but this is just how we behave when taking a selfie in front of a spectacular location. Modern civilisation may have advanced significantly over the past few hundred years, but we’re still constantly glancing at our own versions of the black mirror — our technology screens.